Your Member of Congress may not be overpaid - at least not as overpaid as he or she used to be. Roll Call (subscription required) reports that Congressional salaries have never been lower than they are today - at least as measured against average incomes.

Ire Over Members’ Pay Raises Is Nothing New

July 10, 2006

By Dan Rasmussen,

Roll Call Staff

When Senate Democrats vowed last month to block the Congressional pay raise until lawmakers increase the minimum wage, they were hitting on an issue that has resonated with voters since the adoption of the Constitution.

History shows Americans have rarely been fond of Congressional pay increases and over the past 200 years have shown themselves more than willing to toss out politicians who vote to boost their own salaries.

“It’s always been a hot issue,” said Deputy House Historian Fred Beuttler, ever since a constitutional vagary left Congress with the difficult job of determining the salaries of its own Members way back in 1789.

In their first meeting, lawmakers put aside debates on the Bill of Rights and the permanent location of the federal government to argue about their own wages.

Pennsylvania Sen. Robert Morris (Pro-Administration) called for Senators to be paid more than Representatives. His logic: Senators, whom he considered to be the older and more distinguished statesmen, should not have to live in substandard boarding houses and fraternize with “improper company” — depredations he believed the younger and greener Representatives could handle.

Faced with strong House opposition, Morris’ proposal was defeated, and both chambers agreed on an equal payment of $6 per day.

“The House decided right away that that was not the way to go,” said Associate Senate Historian Don Ritchie.

...In 1856, Congress finally agreed to an annual salary of $3,000, which was about 20 times higher than per capita GDP, according to statistics compiled by historians Louis Johnston and Samuel Williamson.

Perhaps because the change raised few eyebrows, Congress raised its pay again in 1866 and 1873.

But that final salary raise tipped the scales of public opinion, provoking a firestorm over Congressional salaries the likes of which had never before been seen. Members proposed raising their salaries to $7,500 from $5,000, a change that would be retroactive for two years, giving them a one-time bonus of $5,000.

“The expense of living has advanced fearfully beyond what it was in the days of the Revolution,” argued Wisconsin GOP Sen. Matthew Carpenter, as quoted in Sen. Robert Byrd’s (D-W.Va.) “History of the Senate.” “The people of Wisconsin if they send a man here to represent them in the Senate wish him to live how? In the garret of a five-story building on crackers and cheese, to dress in goat skins and sleep in the wilderness?”

But the public did not buy Carpenter’s arguments. The press deemed the increase a “salary grab” and the bonus a “back-pay steal.” Voters were so enraged that when Congress opened in 1874, Members rushed to repeal the bill.

Relative to per capita income, 1873 was the highest point Congressional salaries ever reached. According to Economic History Services, the $7,500 wage would be roughly equivalent to $850,000 today. At the time it was about 40 times per capita GDP.

“In 1856, the public didn’t notice. In 1866, there was another raise. Seven years later, they touched it up, and people started to scream,” Beuttler said. “They didn’t touch the issue for another 30 years.”

Congressional salaries declined relative to average salaries until 1925, when another Congressional pay increase — this time to $10,000 — reversed the trend. But when the Great Depression hit and lawmakers’ income had risen to about 25 times that of the average worker, the government agreed to a rare salary reduction.

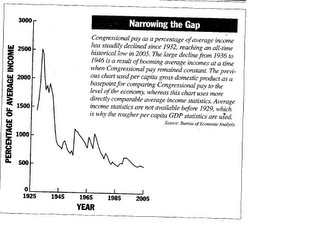

...But according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, salaries never again would be as high in comparison with average Americans as they were in 1932.

Wartime inflation meant that the real value of a lawmaker’s $10,000 salary plummeted. In 1938, Member pay was 19 times the average income. By 1946, it was only seven times the average. Pay hadn’t been so low relative to the average worker since before the Civil War.

Despite consistent Congressional pay increases, a booming economy and steady inflation steadily has narrowed the gap between Congressional pay and per capita income. According to BEA statistics, 2005 Congressional pay was the lowest in history relative to the income of the average American.

In 1967, Congress established a commission to determine salary increases for top-level federal officials. This system was used to increase pay three times, in 1969, 1977 and 1987. On three other occasions, the commission did not recommend an increase.

Since 1991, Congressional pay has increased based on automatic annual comparability adjustments, which are based on surveys of pay in the private sector. Now, instead of passing legislation to enact a pay raise, Members must use a bill to reject an increase. Congress accepted pay increases under this procedure 11 times and rejected them five times...

Just a little perspective.

Back to the top.

1 comment:

If the American people allow Congress to "take away" the

tax cut, when the current law sunsets in 2010, wouldn't it be equally fair for the automatic, ANNUAL Congressional pay raises

also sunset on a date certain, reverting back to an earlier salary?

Just a thought, rarely considered.

Anthony Bruno

Cary, NC

axbruno@hotmail.com

Post a Comment